In 1839 the first Grand National was run. The first race was won by a

horse called Lottery. A Captain Beecher was leading this race when he

fell off his into a stream (brook). The fence where he fell is known as Beecher's Brook.You've seen it in a hundred costume dramas.

Beecher's Brook.You've seen it in a hundred costume dramas.

A young 6 year-old stallion "The Colonel" won the first of two back-to-back triumphs at Aintree by winning the 1869 Grand National whilst being ridden by George Stevens both times. The same George Stevens who won the 1856 National some thirteen years earlier and another set of back-to-back victories on "Emblem" and "Emblematic" in

1863 and 1864 making him one of the true legends of the event. It was

"The Colonel's" second ever steeplechase winning at 100-7. The horse

changed owners over the next twelve months with John Weyman passing over

the honour of bringing back the champion horse to Matthew Evans a year

later.

back-to-back victories on "Emblem" and "Emblematic" in

1863 and 1864 making him one of the true legends of the event. It was

"The Colonel's" second ever steeplechase winning at 100-7. The horse

changed owners over the next twelve months with John Weyman passing over

the honour of bringing back the champion horse to Matthew Evans a year

later.

"The Lamb" became the first ever grey winner of the National in 1868 and one of only two grey horses to win the race, the other being "Nicolaus Silver" almost one hundred years later in 1971. The tiny horse that had been thought to be far too small to win the National found an unusual path to entering the 1868 event after he had originally been sold to a vet, who bought the horse for his daughter. "The Lamb" however

proved to be too much to handle for the young girl allowing him to find

his route into the Grand National for the first time in 1868.

daughter. "The Lamb" however

proved to be too much to handle for the young girl allowing him to find

his route into the Grand National for the first time in 1868.

The horse did however start with fairly good odds at 9-1 and was owned by Lord Poulett who also owned the horse in 1971 when he returned to the race winning again. The jockey George Ede and trainer Ben Land did not return with "The Lamb" though, but still enter the record books associated closely with the small grey horse.Horseback Riding was only available to the wealthy.

Because they were the only ones that had enough money to own or rent and

maintain a horse. Others that weren't so wealthy had to make financial

sacrifices to enjoy the fun that comes

closely with the small grey horse.Horseback Riding was only available to the wealthy.

Because they were the only ones that had enough money to own or rent and

maintain a horse. Others that weren't so wealthy had to make financial

sacrifices to enjoy the fun that comes out of horseback riding. Female

riders needed gloves, boots, and equestrinne tights to fill the costume

recommendations.

out of horseback riding. Female

riders needed gloves, boots, and equestrinne tights to fill the costume

recommendations.

A group of Victorians sitting around the piano. Men in dinner suits, women twitching fans, the daughter of the household bashing out a Mendelsohn standard, polite

applause muffled by white kid gloves, and another round of constipated

dialogue.

standard, polite

applause muffled by white kid gloves, and another round of constipated

dialogue.

If only somebody had thought to check the entertainment listings on the front page of The Times.

Instead of suffering this well-mannered torture, they could have

telegraphed the Cremorne Gardens and booked a table near the bandstand,

scored a few strikes at the American bowling alley, taken in one of the

shows or concerts, guzzled down a curry, danced until four in the

morning, smoked a few opium-laced cigarettes, then returned home on the

tube to negotiate their inevitable hangovers.

and booked a table near the bandstand,

scored a few strikes at the American bowling alley, taken in one of the

shows or concerts, guzzled down a curry, danced until four in the

morning, smoked a few opium-laced cigarettes, then returned home on the

tube to negotiate their inevitable hangovers.

The processes of industrialisation partially account for the scope of these activities. During the reign of Queen Victoria, Britain was transformed from a largely agrarian society to one in which the majority

of the population lived in cities. Those who relocated to these growing

urban environments could no longer, as their parents and grandparents

had done, pursue activities based around the rhythms of village life.

Moreover, industrial jobs offered a precise delineation of work and

leisure time that had never existed in the past.

majority

of the population lived in cities. Those who relocated to these growing

urban environments could no longer, as their parents and grandparents

had done, pursue activities based around the rhythms of village life.

Moreover, industrial jobs offered a precise delineation of work and

leisure time that had never existed in the past. The Victorians were the

first people to have statutory holidays and proscribed days off. The

burgeoning entertainment industry was only too eager to help them fill

that leisure time with recreational pleasures, enticing them into theme

parks, shopping malls, amusement arcades and theatres.

The Victorians were the

first people to have statutory holidays and proscribed days off. The

burgeoning entertainment industry was only too eager to help them fill

that leisure time with recreational pleasures, enticing them into theme

parks, shopping malls, amusement arcades and theatres.

There's a huge disjunction between the received image of nineteenth-century recreation, and the dizzying extent of the pleasures that were available to ordinary Victorians. 'Outside amusements were few,' insists one standard history textbook, 'hence the frequency with which the piano figured in the home.' Nothing could be further from the truth. The lives of Victorians were anything but staid and dull. Indeed, it's hard to think of a public pleasure with which they did not engage with intense, breathless enthusiasm

They were great consumers of recreational drugs, purchased at Boots and knocked back in suburban living rooms all over the country. Most popular was laudanum - a cocktail of opium and alcohol, which is still manufactured for medical use today. This substance wasn't just the tipple of a clique of artsy dopeheads, as it had been in the time of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Thomas De Quincey (although Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, William Gladstone, Jane Carlyle and Florence Nightingale all glugged it back with enthusiasm). Opium was the People's Intoxicant, more freely available in the 19th century than packets of Lambert and Butler are today. The anti-drug laws by which our society is regulated appeared during the First World War, when the government became nervous that the packets of heroin gel that women were buying from Harrods to send to their sweethearts at the Western Front were having detrimental effects upon discipline.More healthily, perhaps, organised team sports achieved a new primacy. Large numbers of Britons learned to swim: a rare talent before the mid-nineteenth-century. The first international cricket match was played in 1868 between British players and an Australian side entirely composed of Aborigines. The Football League was founded in 1888, and had soon generated its own star system, which included figures such as Arthur Wharton, Britain's first black professional footballer, who kept goal for Preston North End and Rotherham, and also found time to break the 100 yards world record, and play professional cricket for Yorkshire and Lancashire.

For the first time, pornography was produced in a volume capable of satisfying a mass readership. Oddly, the industry was founded by a gang of political radicals who used sales of erotica to subsidise their campaigning and pamphleteering: when, in the 1840s, the

widely-anticipated British revolution failed to materialise, these

booksellers and printers found that their former sideline had become too

profitable to relinquish. Lubricious stories such as Lady Pokingham, or, They All Do it

(1881), and hardcore daguerreotypes, photographs and magic lantern

slides, demonstrate the omnivorous nature of Victorian sexuality. Don't

imagine that this material comprised tame pictures of gartered ladies

standing in front of cheese plants; any permutation or peccadillo you

can conceive is represented in the work that has survived from the

period. And it was produced in huge quantities: in 1874, the Pimlico

studio of Henry Hayler, one of the most prominent producers of such

material was loaded up with 130,248 obscene photographs and five

thousand magic lantern slides - which gives some idea of the extent of

its appeal.

the

widely-anticipated British revolution failed to materialise, these

booksellers and printers found that their former sideline had become too

profitable to relinquish. Lubricious stories such as Lady Pokingham, or, They All Do it

(1881), and hardcore daguerreotypes, photographs and magic lantern

slides, demonstrate the omnivorous nature of Victorian sexuality. Don't

imagine that this material comprised tame pictures of gartered ladies

standing in front of cheese plants; any permutation or peccadillo you

can conceive is represented in the work that has survived from the

period. And it was produced in huge quantities: in 1874, the Pimlico

studio of Henry Hayler, one of the most prominent producers of such

material was loaded up with 130,248 obscene photographs and five

thousand magic lantern slides - which gives some idea of the extent of

its appeal.

5 years after Harry Lamplugh won the Grand National as a jockey he was back again winning for a second time, but this time as the trainer of "Cortolvin" the 16-1 outsider. The horse who won while ridden by John Page and was owned by the Duke of Hamilton wasn't really expected to fair that well in 1867, but under the guidance of John Page and Harry Lamplugh, was prepared sufficiently to fly past the opposition and win at the big one Aintree.

"Salamander" did however repay the faith Edward Studd

showed in him by making a full recovery and returning £40,000 from the

huge gamble placed upon him as Alec Goodman rode him to victory.

"Salamander" did however repay the faith Edward Studd

showed in him by making a full recovery and returning £40,000 from the

huge gamble placed upon him as Alec Goodman rode him to victory.

The jockey Henry Coventry

was also cousin of Lord Coventry who owned the two winning horses in

1863 and 1864, while this year's horse owner was Benjamin John Angell,

the same Benjamin John Angell who formed the governing body for horse

racing in 1866 known as the National Hunt Committee.

The jockey Henry Coventry

was also cousin of Lord Coventry who owned the two winning horses in

1863 and 1864, while this year's horse owner was Benjamin John Angell,

the same Benjamin John Angell who formed the governing body for horse

racing in 1866 known as the National Hunt Committee.

Beecher's Brook.You've seen it in a hundred costume dramas.

Beecher's Brook.You've seen it in a hundred costume dramas.

A young 6 year-old stallion "The Colonel" won the first of two back-to-back triumphs at Aintree by winning the 1869 Grand National whilst being ridden by George Stevens both times. The same George Stevens who won the 1856 National some thirteen years earlier and another set of

back-to-back victories on "Emblem" and "Emblematic" in

1863 and 1864 making him one of the true legends of the event. It was

"The Colonel's" second ever steeplechase winning at 100-7. The horse

changed owners over the next twelve months with John Weyman passing over

the honour of bringing back the champion horse to Matthew Evans a year

later.

back-to-back victories on "Emblem" and "Emblematic" in

1863 and 1864 making him one of the true legends of the event. It was

"The Colonel's" second ever steeplechase winning at 100-7. The horse

changed owners over the next twelve months with John Weyman passing over

the honour of bringing back the champion horse to Matthew Evans a year

later.

|

"The Lamb" became the first ever grey winner of the National in 1868 and one of only two grey horses to win the race, the other being "Nicolaus Silver" almost one hundred years later in 1971. The tiny horse that had been thought to be far too small to win the National found an unusual path to entering the 1868 event after he had originally been sold to a vet, who bought the horse for his

daughter. "The Lamb" however

proved to be too much to handle for the young girl allowing him to find

his route into the Grand National for the first time in 1868.

daughter. "The Lamb" however

proved to be too much to handle for the young girl allowing him to find

his route into the Grand National for the first time in 1868.

The horse did however start with fairly good odds at 9-1 and was owned by Lord Poulett who also owned the horse in 1971 when he returned to the race winning again. The jockey George Ede and trainer Ben Land did not return with "The Lamb" though, but still enter the record books associated

closely with the small grey horse.Horseback Riding was only available to the wealthy.

Because they were the only ones that had enough money to own or rent and

maintain a horse. Others that weren't so wealthy had to make financial

sacrifices to enjoy the fun that comes

closely with the small grey horse.Horseback Riding was only available to the wealthy.

Because they were the only ones that had enough money to own or rent and

maintain a horse. Others that weren't so wealthy had to make financial

sacrifices to enjoy the fun that comes out of horseback riding. Female

riders needed gloves, boots, and equestrinne tights to fill the costume

recommendations.

out of horseback riding. Female

riders needed gloves, boots, and equestrinne tights to fill the costume

recommendations.A group of Victorians sitting around the piano. Men in dinner suits, women twitching fans, the daughter of the household bashing out a Mendelsohn

standard, polite

applause muffled by white kid gloves, and another round of constipated

dialogue.

standard, polite

applause muffled by white kid gloves, and another round of constipated

dialogue.

...it's hard to think of a public pleasure with which they did not engage with intense, breathless enthusiasm.

and booked a table near the bandstand,

scored a few strikes at the American bowling alley, taken in one of the

shows or concerts, guzzled down a curry, danced until four in the

morning, smoked a few opium-laced cigarettes, then returned home on the

tube to negotiate their inevitable hangovers.

and booked a table near the bandstand,

scored a few strikes at the American bowling alley, taken in one of the

shows or concerts, guzzled down a curry, danced until four in the

morning, smoked a few opium-laced cigarettes, then returned home on the

tube to negotiate their inevitable hangovers.The processes of industrialisation partially account for the scope of these activities. During the reign of Queen Victoria, Britain was transformed from a largely agrarian society to one in which the

majority

of the population lived in cities. Those who relocated to these growing

urban environments could no longer, as their parents and grandparents

had done, pursue activities based around the rhythms of village life.

Moreover, industrial jobs offered a precise delineation of work and

leisure time that had never existed in the past.

majority

of the population lived in cities. Those who relocated to these growing

urban environments could no longer, as their parents and grandparents

had done, pursue activities based around the rhythms of village life.

Moreover, industrial jobs offered a precise delineation of work and

leisure time that had never existed in the past. The Victorians were the

first people to have statutory holidays and proscribed days off. The

burgeoning entertainment industry was only too eager to help them fill

that leisure time with recreational pleasures, enticing them into theme

parks, shopping malls, amusement arcades and theatres.

The Victorians were the

first people to have statutory holidays and proscribed days off. The

burgeoning entertainment industry was only too eager to help them fill

that leisure time with recreational pleasures, enticing them into theme

parks, shopping malls, amusement arcades and theatres.

There's a huge disjunction between the received image of nineteenth-century recreation, and the dizzying extent of the pleasures that were available to ordinary Victorians. 'Outside amusements were few,' insists one standard history textbook, 'hence the frequency with which the piano figured in the home.' Nothing could be further from the truth. The lives of Victorians were anything but staid and dull. Indeed, it's hard to think of a public pleasure with which they did not engage with intense, breathless enthusiasm

They were great consumers of recreational drugs, purchased at Boots and knocked back in suburban living rooms all over the country. Most popular was laudanum - a cocktail of opium and alcohol, which is still manufactured for medical use today. This substance wasn't just the tipple of a clique of artsy dopeheads, as it had been in the time of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Thomas De Quincey (although Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, William Gladstone, Jane Carlyle and Florence Nightingale all glugged it back with enthusiasm). Opium was the People's Intoxicant, more freely available in the 19th century than packets of Lambert and Butler are today. The anti-drug laws by which our society is regulated appeared during the First World War, when the government became nervous that the packets of heroin gel that women were buying from Harrods to send to their sweethearts at the Western Front were having detrimental effects upon discipline.More healthily, perhaps, organised team sports achieved a new primacy. Large numbers of Britons learned to swim: a rare talent before the mid-nineteenth-century. The first international cricket match was played in 1868 between British players and an Australian side entirely composed of Aborigines. The Football League was founded in 1888, and had soon generated its own star system, which included figures such as Arthur Wharton, Britain's first black professional footballer, who kept goal for Preston North End and Rotherham, and also found time to break the 100 yards world record, and play professional cricket for Yorkshire and Lancashire.

For the first time, pornography was produced in a volume capable of satisfying a mass readership. Oddly, the industry was founded by a gang of political radicals who used sales of erotica to subsidise their campaigning and pamphleteering: when, in the 1840s,

the

widely-anticipated British revolution failed to materialise, these

booksellers and printers found that their former sideline had become too

profitable to relinquish. Lubricious stories such as Lady Pokingham, or, They All Do it

(1881), and hardcore daguerreotypes, photographs and magic lantern

slides, demonstrate the omnivorous nature of Victorian sexuality. Don't

imagine that this material comprised tame pictures of gartered ladies

standing in front of cheese plants; any permutation or peccadillo you

can conceive is represented in the work that has survived from the

period. And it was produced in huge quantities: in 1874, the Pimlico

studio of Henry Hayler, one of the most prominent producers of such

material was loaded up with 130,248 obscene photographs and five

thousand magic lantern slides - which gives some idea of the extent of

its appeal.

the

widely-anticipated British revolution failed to materialise, these

booksellers and printers found that their former sideline had become too

profitable to relinquish. Lubricious stories such as Lady Pokingham, or, They All Do it

(1881), and hardcore daguerreotypes, photographs and magic lantern

slides, demonstrate the omnivorous nature of Victorian sexuality. Don't

imagine that this material comprised tame pictures of gartered ladies

standing in front of cheese plants; any permutation or peccadillo you

can conceive is represented in the work that has survived from the

period. And it was produced in huge quantities: in 1874, the Pimlico

studio of Henry Hayler, one of the most prominent producers of such

material was loaded up with 130,248 obscene photographs and five

thousand magic lantern slides - which gives some idea of the extent of

its appeal.

5 years after Harry Lamplugh won the Grand National as a jockey he was back again winning for a second time, but this time as the trainer of "Cortolvin" the 16-1 outsider. The horse who won while ridden by John Page and was owned by the Duke of Hamilton wasn't really expected to fair that well in 1867, but under the guidance of John Page and Harry Lamplugh, was prepared sufficiently to fly past the opposition and win at the big one Aintree.

|

The 1866 Grand National was won by "Salamander" a 40-1 outsider with larger odds than any winner for years. The horse had been born with a crooked leg and was thought to be near to worthless, with it being bought for a bargain price by Mr. Edward Studd of Rutland when in a terrible state.

"Salamander" did however repay the faith Edward Studd

showed in him by making a full recovery and returning £40,000 from the

huge gamble placed upon him as Alec Goodman rode him to victory.

"Salamander" did however repay the faith Edward Studd

showed in him by making a full recovery and returning £40,000 from the

huge gamble placed upon him as Alec Goodman rode him to victory.

|

"Alchibiade" won the 1865 Grand National ridden by Captain Henry Coventry of the Grenadier Guards who only ever raced in one National. Starting at 100-7, the horse trained by Mr. Cornell ran a fantastic race battling hard to beat all others to victory.

The jockey Henry Coventry

was also cousin of Lord Coventry who owned the two winning horses in

1863 and 1864, while this year's horse owner was Benjamin John Angell,

the same Benjamin John Angell who formed the governing body for horse

racing in 1866 known as the National Hunt Committee.

The jockey Henry Coventry

was also cousin of Lord Coventry who owned the two winning horses in

1863 and 1864, while this year's horse owner was Benjamin John Angell,

the same Benjamin John Angell who formed the governing body for horse

racing in 1866 known as the National Hunt Committee.

bO!~~60_12.JPG)

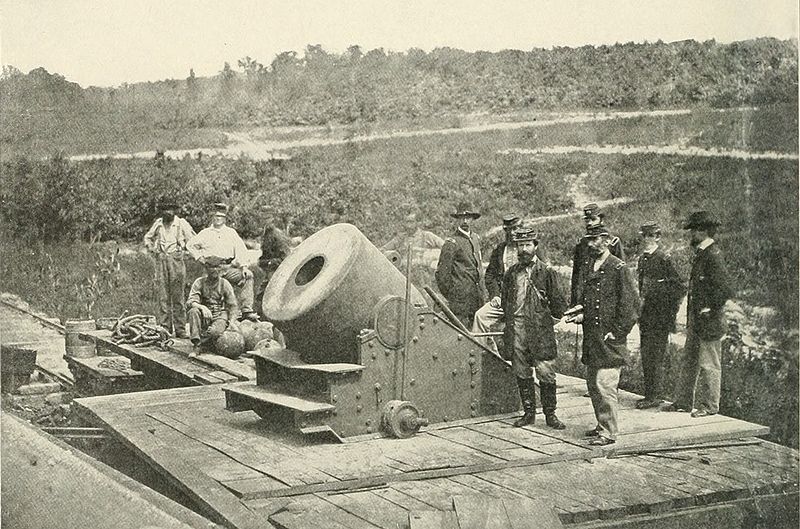

Another common term used in the United States during the American Civil War was "skirmisher". Throughout history armies have used skirmishers to break up enemy formations and to thwart the enemy from flanking the main body of their attack force. They were deployed individually on the extremes of the moving army primarily to scout for the possibility of an enemy ambush. Consequently, a "skirmish" denotes a clash of small scope between these forces.

Another common term used in the United States during the American Civil War was "skirmisher". Throughout history armies have used skirmishers to break up enemy formations and to thwart the enemy from flanking the main body of their attack force. They were deployed individually on the extremes of the moving army primarily to scout for the possibility of an enemy ambush. Consequently, a "skirmish" denotes a clash of small scope between these forces.

Battle of Spotsylvania Court House in May 1864 by a sniper 800 yards away. While he was placing field guns behind his front line, Sedgwick waved toward the distant Rebel sharpshooters and laughingly enjoined his gunners to ignore their sporadic shots: “What are you dodging for? They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance!” Seconds later, a bullet smashed into Sedgwick’s face, killing him instantly.

Battle of Spotsylvania Court House in May 1864 by a sniper 800 yards away. While he was placing field guns behind his front line, Sedgwick waved toward the distant Rebel sharpshooters and laughingly enjoined his gunners to ignore their sporadic shots: “What are you dodging for? They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance!” Seconds later, a bullet smashed into Sedgwick’s face, killing him instantly.

Russian musketeers in the Crimean War, which was fought from 1854 to 1856 on Russia’s Black Sea coast. Thereafter, all armies had re-equipped with rifles, which were essentially muskets with grooved barrels that would “take” the soft lead of a bullet and fling it in a tight, spiraling shot at a distant target. Whereas musket rounds rolled and hopped like knuckle balls, rifle rounds screamed in like fastballs—straight down the pipe.

Russian musketeers in the Crimean War, which was fought from 1854 to 1856 on Russia’s Black Sea coast. Thereafter, all armies had re-equipped with rifles, which were essentially muskets with grooved barrels that would “take” the soft lead of a bullet and fling it in a tight, spiraling shot at a distant target. Whereas musket rounds rolled and hopped like knuckle balls, rifle rounds screamed in like fastballs—straight down the pipe.

one of dozens of Union light infantry outfits, required feats of accuracy: at 600 feet, 10 consecutive shots at an average of five inches from the bull’s-eye. Col. Hiram Berdan, who was ordered by Gen. Winfield Scott to create two entire sharpshooter regiments from companies raised in the various states of the Union, was himself a famous crack shot—the best in the Union army.

one of dozens of Union light infantry outfits, required feats of accuracy: at 600 feet, 10 consecutive shots at an average of five inches from the bull’s-eye. Col. Hiram Berdan, who was ordered by Gen. Winfield Scott to create two entire sharpshooter regiments from companies raised in the various states of the Union, was himself a famous crack shot—the best in the Union army. President Jefferson Davis from 200 yards and score repeated head shots. One story had him asking a spectator, “Where shall I place the next one?” “In the right eye,” came the answer, and the next shot tore away the right eye.

President Jefferson Davis from 200 yards and score repeated head shots. One story had him asking a spectator, “Where shall I place the next one?” “In the right eye,” came the answer, and the next shot tore away the right eye. When it was fitted with a telescopic sight, the Whitworth had what was grimly called “killing accuracy” of 1,500 yards. The Whitworth barrel was drilled in a hexagonal pattern and fired a bullet shaped like a threaded nut. Gen. William Haines Lytle,

When it was fitted with a telescopic sight, the Whitworth had what was grimly called “killing accuracy” of 1,500 yards. The Whitworth barrel was drilled in a hexagonal pattern and fired a bullet shaped like a threaded nut. Gen. William Haines Lytle, the Ohio-born Union soldier-poet, was shot off his horse and killed by a Whitworth-armed Confederate sharpshooter at the Battle of Chickamauga

the Ohio-born Union soldier-poet, was shot off his horse and killed by a Whitworth-armed Confederate sharpshooter at the Battle of Chickamauga  in September 1863. (Lytle had 10 months earlier written his last poem—“Lines on My Thirty-Sixth Birthday”—which, true to its Byronic title, predicted his imminent death in battle.)

in September 1863. (Lytle had 10 months earlier written his last poem—“Lines on My Thirty-Sixth Birthday”—which, true to its Byronic title, predicted his imminent death in battle.)