Saturday 31 March 2012

Sunday 25 March 2012

Saturday 24 March 2012

Friday 23 March 2012

the french invasion

The annals of history record the name of Hastings as the site of the last invasion of Britain by French, well Norman, forces in 1066. True, this was the last successful invasion. However, little is reported about the French invasion of Fishguard, which took place in southwest Wales in 1797, nor of the brave resistance offered by "Jemima Fawr" (Jemima the Great), who single-handedly captured twelve of the invading soldiers.

The annals of history record the name of Hastings as the site of the last invasion of Britain by French, well Norman, forces in 1066. True, this was the last successful invasion. However, little is reported about the French invasion of Fishguard, which took place in southwest Wales in 1797, nor of the brave resistance offered by "Jemima Fawr" (Jemima the Great), who single-handedly captured twelve of the invading soldiers.

In 1797, Napoleon Bonaparte was busy conquering in central Europe. In his absence the newly formed French revolutionary government, the Directory, appears to have devised a 'cunning plan' that involved the poor country folk of Britain rallying to the support of their French liberators. Obviously the Directory had recently taken delivery of some newly liberated Brandy!

On Wednesday, February 22, the French warships sailed into Fishguard Bay, to be greeted by canon fire from the local fort. Unbeknown to the French the cannon was being fired as an alarm to the local townsfolk, nervously the ships withdrew and sailed on until they reached a small sandy beach near the village of Llanwnda. Men, arms and gunpowder were unloaded and by 2 am on the morning of Thursday, February 23rd, the last invasion of Britain was completed. The ships returned to France with a special despatch being sent to the Directory in Paris informing them of the successful landing.The French invasion force comprising some 1400 troops set sail from Camaret on February 18, 1797. The man entrusted by the Directory to implement their 'cunning plan' was an Irish-American septuagenarian, Colonel William Tate. As Napoleon had apparently reserved the cream of the Republican army for duties elsewhere in Europe, Colonel Tate's force comprised of a ragtag collection of soldiers including many newly released jailbirds. Tate's orders were to land near Bristol, England's second largest city, and destroy it, then to cross over into Wales and march north onto Chester and Liverpool. From the outset however all did not proceed as detailed in the 'cunning plan'. Wind conditions made it impossible for the four French warships to land anywhere near Bristol, so Tate moved to 'cunning plan' B, and set a course for Cardigan Bay in southwest Wales.

The French invasion force upon landing appear to have run out of enthusiasm for the 'cunning plan', perhaps a result of those years of prison rations, they seem to have been more interested in the rich food and wine the locals had recently removed from a grounded Portuguese ship. After a looting spree, many of the invaders were too drunk to fight and within two days, the invasion had collapsed, and Tate's force surrendered to a local militia force led by Lord Cawdor on February 25th 1797.

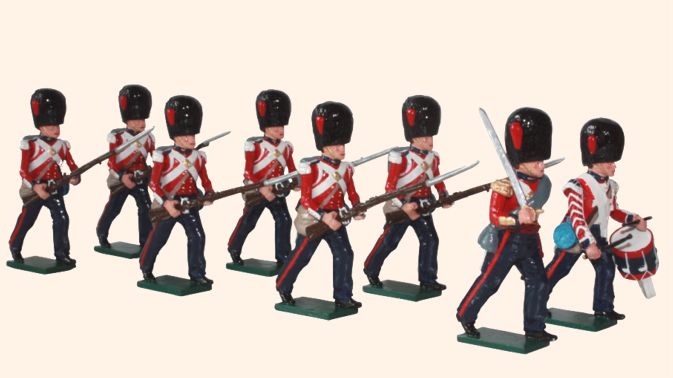

Strange that the surrender agreement drawn up by Tate's officers referred to the British coming at them "with troops of the line to the number of several thousand." No such troops were anywhere near Fishguard, however, hundreds, perhaps thousands of local Welsh women dressed in their traditional scarlet tunics and tall black felt hats had come to witness any fighting between the French and the local men of the militia. Is it possible that at a distance, and after a glass or two, those women could have been mistaken for British army Redcoats?

Prussia's shattering defeat of France in 1870 did not mean the end of invasion fear in Britain. As the traditional enemy against which massive new defences had been constructed during the 1860s, France had been removed as a threat but the manner of its removal caused new fears. Revealed as efficient, militaristic, ruthless and ambitious for world power and territory, Germany was now seen by Britain as the potential new enemy - the next invader. This new fear was expressed in an unusual form as the polemical invasion novel and the (usually jingoistic) popular magazine or newspape

The non-arrival of the Germans on Britain's shores during the 1870s did not cool the fevered imaginations of the alarmist novelists. The next target for invasion terror was the proposed Channel Tunnel; in 1882 a scheme to build a railway tunnel from Calais to Dover was proposed in Parliament. The titles of the novels this scheme provoked - England in Danger, The Seizure of the Channel Tunnel, The Battle of the Channel Tunnel - reveal the popular concerns that were shared by Queen Victoria, who called the tunnel 'objectionable', and by Lord Randolph Churchill who probably summed up public opinion when he observed that 'the reputation of England has hitherto depended on her being, as it were, Virgo intacta'.

During their two days on British soil the French soldiers must have shaken in their boots at mention of name of "Jemima Fawr" (Jemima the Great). The 47-year-old Jemima Nicholas was the wife of a Fishguard cobbler. When she heard of the invasion, she marched out to Llanwnda, pitchfork in hand and rounded up 12 Frenchmen. She brought them into town and promptly left to look for some more. - Men of Harlech meet your match!

Objections from all levels of society stopped the project after a couple of miles of tunnel had been excavated from each coast, but no sooner had this 'threat' been stymied than another appeared. As if to underline the almost manic nature of Britain's late 19th century invasion fear, France, so suddenly thrashed by the Prussia, made a sudden reappearance in the mid 1880s as enemy number one. What if, wondered some more pessimistic military analyst, France and Russia joined forces to invade England to strike with terrifying ease at the very heart of the British Empire - London. The capital's defences were outmoded and organised primarily for the defence of its dockyards at Tilbury and Chatham while the regular army was small and scattered over much of the world policing the empire.The first of these alarmist articles, which appeared initially in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine and then in sixpenny-book form, was the Battle of Dorking. Published in 1871 and written by George Chesney, it described vividly the way in which a German invasion would affect ordinary households and argued that Britain was, due to its complacency and reductions on military spending, vulnerable to attack from Germany.

The capital's defences were outmoded and organised primarily for the defence of its dockyards at Tilbury and Chatham...

A flurry of learned and sensational articles and anxious debates in Parliament stirred up great public and political concern. Typical was a little book, published anonymously in 1885 and entitled The Siege of London. It envisaged a French invasion that culminated in a tremendous battle in Hyde Park, the capitulation of London and the eventual loss of India, the Cape, Gibraltar and Ireland.

The consequences in Britain of this new fear of France was an increase in the size and improvement in training and equipment of Britain's volunteer forces, and the construction, to the southeast of London, of a ring of fortified mobilisation centres, notably at Box Hill and Henley Grove near Guildford. These centres were to act as supply depots and as rallying points around which local volunteers could muster and from which they could draw arms

With the signing of the Entente Cordiale between France and Great Britain the fear of French invasion was finally and formally laid to rest in 1904. Attention was now firmly focused on Germany as the future foe and it was at this moment that Britain's most famous invasion novel was published. The Riddle of the Sands, written by Erskine Childers and published in 1903, focuses on a cunning German invasion plot with troops sneaking across the North Sea hidden in fleets of coal barges. Although the technique by which Childers envisaged a German invasion was novel, the essential method of attack - a sea-borne onslaught - was entirely traditional. This is hardly surprising since, around 1900, an arms race between Britain and German was in full swing and the focus of this competition was the battleship.

In 1898 and 1900 Germany passed Navy Laws which identified the types and numbers of warships required and which provided permission and cash for the project. To justify the vast expense of the undertaking, these laws also identified a specific and dangerous enemy that this fleet was being built to counter: 'For Germany, the most dangerous naval enemy at the present time is England.... Our fleet must be constructed so that it can unfold its greatest military potential between Heliogoland and the Thames....' As the construction of a massive fleet was being debated and agreed by the Kaiser and his military and political advisors another undertaking, of great relevance to future German naval strategy, was being completed. The Kiel Canal, which opened in 1895, provided the German navy with a fast connection between the Baltic and the North Sea and so allowed its different fleets to work in close co-operation.The German bid to become a world power with its own far-flung empire was very much the personal ambition of the young Kaiser Wilhelm II who came to power in 1888. An overseas empire was needed, argued Germans, not only for prestige but because the German economy would atrophy if it did not acquire colonies that could provide raw materials and markets for finished products. To acquire, service and protect these colonies a strong German naval and merchant fleet was essential, but the construction of a powerful fleet of warships, making Germany into a significant maritime power, brought it into direct conflict with Britain. Since the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 Britain's Royal Navy had been the dominant fighting fleet in the world; now Germany was challenging this position.

Monday 19 March 2012

germans at dieppe

bombarded with enemy fire, surrounded by dead or dying Canadian soldiers, and in the midst of one of the worst military disasters in Canada's history.

bombarded with enemy fire, surrounded by dead or dying Canadian soldiers, and in the midst of one of the worst military disasters in Canada's history. | ||

"I noticed a handful of soldiers spread out on the ground," the Canadian recalled, "with their heads turned toward the parapets, as if waiting for the order to move. So I crawled toward one of them, I shook him and spoke to him, but he didn't answer. He was dead. I did the same with a few others, but in vain. They were all dead."

The attack on Dieppe, codenamed Jubilee, was supposed to be a quick in-and-out raid. It was intended to placate the Soviet allies who were fighting the Germans alone on the Eastern Front. The raid was also planned to test German defences.

Five thousand Canadians soldiers made up the bulk of the assault force. Many had been training in England since the start of the war.

On a clear summer night, 237 ships slipped quietly across the English Channel, hoping to surprise the Germans at Dieppe. But part of the landing force encountered a small German convoy, that alerted the German defenses. As the ships approached the Dieppe beach at 5:20 a.m., it was clear that they had lost the element of surprise.

Captain Denis Whitaker and the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry landed on the beach at dawn. His first glance revealed he was in a trap. As the Canadians stepped onto the beaches, they were mowed down.

"The ramp dropped," Whitaker recalled. "I led 30 odd men of my platoon in a charge about twenty-five yards up the stony beach. We fanned out and flopped down just short of a huge wire obstacle. Bullets flew everywhere. Enemy mortar bombs started to crack down. Around me, men were being hit and bodies were piling up, one on top of the other. It was terrifying."

Dieppe had been a French resort town, its stony beach and casino popular among Parisians seeking relief during the sticky summer months. Whitaker's men moved toward the casino, and routed the Germans who were using it for cover. Miraculously, Whitaker and a few of his men reached the town and a small wooden building.

"We flung ourselves on the cement floor and discovered that the whole shack had been used as a latrine. It was impossible to move, as the mortaring continued without interruption; we lay in this crap for twenty or thirty minutes, feeling great revulsion for every German alive!"

Casualties were already high but radio communications poor and commanders on the ships were not aware of the extent of the disaster .jpg) unfolding. Reserve troops were ordered into the slaughter.

unfolding. Reserve troops were ordered into the slaughter.

.jpg) unfolding. Reserve troops were ordered into the slaughter.

unfolding. Reserve troops were ordered into the slaughter.Lieutenant-Colonel Dollard Menard, 29, and his 600 men of the Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal waded toward the beach under heavy fire.

"I think that I must have made no more than three steps before I was hit by a bullet for the first time and knocked to the ground," remembered Menard. "A bullet is like a razor cut to the face. At first you don't feel the pain. I was hit a second time. It seemed to explode all around me. I was no longer sure I was still in one piece. The bullet hit me in the cheek and tore my face pretty badly. I managed to get up when I was hit for the third time, this time in my right wrist."

Finally the order to retreat was given.

"I was leaving the beach when I was hit in the right leg just below the knee, but I continued on," said Menard. "The last bullet hit me below the right ankle and nailed me to the ground for good. I began to pray."

Captain Whitaker was trying to lead his surviving men back from the casino, toward the beach, to pull out.

"The worst part was the dash for the boats amid a hail of bullets and mortar or shellfire. Apart from trying to help the wounded, it was every man for himself. I expected every step to be my last."

Whitaker made it back to the boats, the only Canadian officer to survive unscathed. Menard was pulled to safety by his men to boat and survived his five bullet wounds.

The Royal Navy managed to rescue several hundred men. Another 2,000, almost all of them Canadian, watch helplessly as the last British naval vessel disappeared over the horizon. They became prisoners of war.

At home, headlines proclaimed the success of Dieppe. But casualty lists provided a telling rebuke. Of the 5,000 Canadians who landed at Dieppe, 907 were dead, 586 wounded.

Canadians had been victims of bad military planning as much as German bullets in the disaster at Dieppe.

Historians debate the value of Dieppe. Some say it provided an invaluable lesson for subsequent coastal assaults on North Africa, Sicily and Italy in the years to come. Others say it was a military debacle undertaken for political reasons and yielded little that was new in terms of military strategy.

In England, Albert Kirby and other Canadian survivors were left to deal with the aftermath of Dieppe.

"What a mixture of feeling went through my body surveyed the shambles throughout the harbour. So relieved to be home. So happy to be in one piece. So ashamed to have come home alone. So proud of the way the Camerons went to their deaths. So sad that they seemed to have been wasted. So angry that I was even a part of something so confusing, and apparently unrewarding, without even knowing what I was doing or exactly where I had been."

Friday 16 March 2012

britains foreign legion

The author A. R. Cooper joined the French Foreign Legion in 1914 at the age of fifteen and a half after an adventurous few years at sea. He enlisted at Algiers under the name of Cornelis Jean de Bruin and was sent to Fort St. Therese at Oran and thence to Sidi Bel Abbes, the headquarters of the Legion in Algeria.

At Sidi Bel Abbes we were met by a sergeant of the Legion, taken to the barracks and marched in through the great central gate.

On each side of a tree-bordered avenue are the four-storied buildings in which the men live; at the end of the avenue are the offices and beyond (a place very well known to every Légionnaire!) the canteen, also the wash-house, stores and other buildings on the right of the main building is the Salle d'Honneur, where all the trophies and flags of the Legion are kept, and beyond that the prison, all enclosed by a high wall. We arrived at Sidi Bel Abbe's on the fourteenth of October, 1914. Everything was in a state of commotion. The 3rd Battalion had just received orders for active service. We recruits were sent right away to the stores to get our kit, rations, rifles and ammunition and then were told to fall in with the rest. A pretty raw and awkward bunch we must have been.

The kit issued to us in those days consisted of képi, which was red with a blue band, blue tunic, red trousers, and a short vest which we called veste de singe, an overcoat and the blue woollen belt which it is compulsory to wear over our tunics as a precaution against dysentery. The couvre nuque was also issued but, in spite of the fact that in films about the Legion the officers and men are always shown wearing it, day and night, this is not so in reality. It is never worn. The only use to which it is put by Légionnaires is to strain their coffee or even water when it is very muddy! The epaulettes, which are also featured in films and fiction have not been worn since 1907. The only epaulette a Legion soldier wears is a little blue rosette of felt which he sews on his right shoulder in order to hitch his rifle over it. When we were in the Dardanelles in 1915 blue linen trousers called salopettes were issued to us to wear over our red ones. During the war, when the French troops got their bleu horizon, we were given khaki and since then all the French Colonial troops have worn khaki. The French Government bought up all the American uniforms at the end of the war.

Within a few hours of our arrival at Sidi Bel Abbes the battalion was entrained for Perrigaux. As we got there we heard firing and learned that the Arabs had attacked the town and that we had to push them back into the mountains. This attack on Perrigaux was the last Arab revolt in Algeria.

Our forces consisted of one battalion of the Legion, some French Colonial troops and a few Tirailleurs.

We dug a trench. We could see the Arabs only about two hundred yards away and knew that there were a lot more that we could not see, among the rocks at the foot of the hills. The rifle that was issued to us in those days was the fusil gras which had been in use since 1870. It was monstrously heavy and fired great big bullets. I had no idea how to use it but I lay down in the trench next to an old soldier and watched what he did. The first shot I fired there was a terrible kick which made my shoulder sore for days! I opened the bolt very carefully and slowly for fear of what would happen so that the ejector did not work and I had to poke the cartridge case out with a pencil!

The soldier next me laughed and showed me how to use the rifle and after that it was better and I began to enjoy firing it.

After an hour of this we were ordered to fix bayonets and charge. In a charge like this, it is the old soldiers, who have experience of colonial warfare and know how to take cover and watch out for the Arabs, who get through. On that charge nearly all the recruits who came up with me were killed.

I was not at all afraid and to my own surprise I was not even excited. I seemed to feel quite cool ; in those days I was unconscious of danger. I did not know what it meant. Every one was all over the place. I found myself face to face with an Arab and plunged my bayonet into him, but in doing so I turned it so that I could not get it out again and had to leave it in his body. The Arabs do not like facing steel and they began to ran away towards the mountains with our troops after them in any sort of order.

I had already been told that for every enemy killed a Légionnaire cuts a notch in his rifle and as I went on I got out my knife and started to make a notch on mine. It was very hot and I was dead tired with running over the rough ground and carrying the heavy rifle and kit, and so I sat down on a rock to rest. Suddenly I saw a party of Arabs quite near to me on the right. They closed round me and I realised that I was their prisoner but, not really knowing what that meant, I was not frightened and thought it best to be friendly so I offered them cigarettes. They took them and also took my cartridges away from me, but left me to carry the heavy rifle. I could not under-stand what they said but something in their faces and gestures alarmed me in an unexpected way, and when one of them started to put his hands on me in a nauseating, caressing way I upped with the butt of the rifle and smashed his head in. That ended all friendly relationship with my captors

When they got me back to their camp I was handed over to the women. It is the women who do the torturing. On the way up to Perrigaux in the train an old soldier had been telling of his adventures and had talked of having been taken prisoner by the Arabs. I remembered his saying that if this should happen to a man the only thing to do to escape torture was to pretend to be mad as the Arabs think that a madman is "possessed" by a spirit and will not touch him. So I thought I had better do this and I started catching flies where there were none, catching at my own thumb and making any idiotic face and gesture I could think of. When I saw them draw back from me I wanted to laugh, but I managed not to do so.

They put some food near me which I was glad of by then and in the evening they brought me to the Marabou (a sort of holy man or priest) who could speak French and he questioned me about the strength of the battalion. I don't think I even knew, but, anyway, I made up some tremendous number and all the time I was playing the fool to make him believe me mad.

The Arabs evidently did not think much of me as a prisoner for that night they took me down to the plain near where we had been fighting that day and signed to me to go back to our lines. But they had taken my rifle away from me and that bothered me very much. I did not want to go back without it. Already I had been made to understand that it was a terrible offence in the Legion to lose any part of your kit or equipment but also my rifle had that notch in it for my" first man." I went on for a few hundred yards towards Perrigaux and then I hid behind a bush and began wondering how on earth I could get my rifle back. The rest of the night I lay out there between the lines.

Early in the morning the Legion started to attack again and a lot of them came right past me. The Arabs ~ere shooting from behind their boulders and bushes and the Arab marksmen are deadly sure. They have any kind of rifle they can get hold of and they do not use the sights, but put two fingers on the barrel when they aim. A Legion soldier fell dead, shot through the head, within a yard of where I was hiding. Then I came out, made sure he was lifeless, picked up his rifle and joined in the attack.

When it was over I went to my Captain and reported. I told him all that had happened. He seemed to find it amusing, as I did when I started to talk about it, and he laughed and said he was pleased with me, that I was a good soldier. I felt very proud of that.

We quelled the Arab revolt in, I think, four or five days and then we went back to Sidi Bel Abbes.

When we were back in barracks I got in touch with an old soldier who promised to show me the ropes and put me wise to the ways of the Légionnaires. He was a very nice fellow, a bugler from Brittany called Le Gonnec.

When a man joins the French Foreign Legion the first thing he has to learn is the base de la discipline - the Legion's code.

It is : "La disciphne étant la force principale de la Légion il importe que tous superieurs obtiennent de ses subordonn6s une obeissance entiere et une soumission de tous les instants, que les ordres soient execute's instantanément, sans hesitation ni murmure, les autorités qui les donnent en sont responsable et Ia reclamation n'est permise a l'inférieur que lorsque qu'il a obei."*

*Discipline being the principal strength of the Legion it is essential that all superiors receive from their subordinates absolute obedience and submission on all occasions. Orders must be executed instantly without hesitation or complaint. The authorities who give them are responsible for them and an inferior is only permitted to make an objection after he has obeyed.

The second thing a Legionnaire must learn is how to get drunk when he has no money to buy wine!

In I914 there were three battalions and each battalion had four companies.

My company was the 9th of the 3rd battalion of the 1st regiment commanded by Captain Rousseau. He was a splendid officer and understood his men, having been a ranker himself. His old mother used to keep a canteen in Sidi Bel Abbes. Although there were the sergeants and corporals between them and the men, the good officers always studied their men and knew their characters, when to overlook their faults, when to punish, and how to get the best out of them.

A second-class soldier is an ordinary private. First-class soldiers are rare and are not thought anything of as, in order to gain this nebulous distinction, a man must have no punishment, and that is practically impossible for a real Légionnaire. The best soldiers in the fighting line spend a great deal of their time in prison when their battalion is in barracks.

I always hated parades and one morning when the sergeant who was drilling us had made us stand to attention and slope arms several dozen times, I began obeying slackly, just bending my knee and not moving my feet apart at the word repos and, when he went for me, I threw my rifle down on the ground. For this I was tied to a tree for the rest of the morning, with the woollen belt which, as I have said, we all wore, by orders, over our tunice. Afterwards I was reported to the Captain.

When he asked me why I had behaved like that, I said: I am intelligent enough to know how to stand at attention and slope arms after doing it once; I don't need to go on doing it fifty times an hour."

As a matter of fact, I was rather a favourite with Captain Rousseau. He knew my age, as indeed they all did (unofficially, of course) and he chose to overlook both my "crime" and my cheek.

He cautioned me that to refuse to obey a command meant court-martial and prison and told me not to do it again. But by his orders I was given a job in the store-room and so escaped those eternal and infernal parades. .

In February, 1915, it was posted in orders that any man who wished to do so could volunteer for active service. I think nearly the whole battalion wanted to. I was for rushing off to find the Captain to put my name down then and there. Some one tried to stop me and explained that I must go to the Corporal, who would forward my name to the Sergeant and he would give it to the Lieutenant for the Captain.

"Not I!" I called to them, as I went off. "I'm going straight to God, not to all his Saints first."

I found Captain Rousseau in the mess-room, saluted and said: If you please, sir, will you put my name down for active service ?

"That's all right, de Bruin" - he smiled -"You're down already.”

From Tiaret we were sent to Oran where we camped in an old Roman arena which is surrounded by a very high wall, the idea being that this would make it difficult for us to break camp and go into the town to drink. As a matter of fact, the authorities are never very optimistic about the success of their expedients in this direction. They know the Légionnaires too well. Those of us who were determined to get into the town that night fastened our leather belts together and so managed to 8cale those noble Roman walls.

Many are the ways in which a Legion soldier will earn drinks or the money to buy them. I used to go into the café and entertain people by blowing fire out of my mouth (a trick easily done with petrol) eating the red-hot end of my cigarette (the doctors say it is good for the stomach I) and piercing my cheeks with needles or pins. This does not hurt in the least if you do it quickly enough. The price of these edifying exhibitions was enough wine to keep me happy for the evening.

So well do the authorities know what is going on that they send out patrols to bring the truants back under arrest, some-times unconscious. But there is no punishment on the eve of going into action.

The morning after we camped at Oran, half the battalion was missing, but Legionnaires do not desert when they know they are going to fight and gradually they came in. Some turned up even without hats and other parts of their kit when we were on the quay ready to embark, but the battalion left Oran full strength.

We went on La France, which had been a passenger boat plying between Marseilles to Tunis. She had been converted into a troopship. At Malta we had to stay on board and we were disembarked at Alexandria. There we were attached to the Rdgiment de Marche d'Afrique, composed of volunteers from regular French regiments, under General d'Amade. We camped at the back of the Victoria Hospital on English territory. We still did not know our destination.

We had been kept hanging about, on the boat and at Alexandria, for over two months. There was a shortage of cigarettes and wine and there was a faction in the battalion which began to be actively discontented and to discuss whether it would not be a good thing to desert. We were on English territory and the idea was that if we could get away we might join the English forces and see some of the fighting for which we had volunteered. I was young and easily led and anything that sounded like an adventure was in my line so I threw in my lot with about forty men who decided to get away. It was a very abortive effort at desertion and we were caught and brought back to camp under arrest.

Then orders came through that there was to be a review. Whether this was intended to occupy us or impress some one else, I don't know; but on account of it those under arrest were released and put back into the lines. When the review was over we were again put under arrest.

At last we were embarked on the Bien Hoa, one of the ships which had relieved Casablanca when the town was captured by the Arabs in 1907.

It was a relief to know that we were on our way somewhere, presumably to the fighting line and, on board, those under arrest were released.

At Sidi Bel Abbes we were met by a sergeant of the Legion, taken to the barracks and marched in through the great central gate.

On each side of a tree-bordered avenue are the four-storied buildings in which the men live; at the end of the avenue are the offices and beyond (a place very well known to every Légionnaire!) the canteen, also the wash-house, stores and other buildings on the right of the main building is the Salle d'Honneur, where all the trophies and flags of the Legion are kept, and beyond that the prison, all enclosed by a high wall. We arrived at Sidi Bel Abbe's on the fourteenth of October, 1914. Everything was in a state of commotion. The 3rd Battalion had just received orders for active service. We recruits were sent right away to the stores to get our kit, rations, rifles and ammunition and then were told to fall in with the rest. A pretty raw and awkward bunch we must have been.

The kit issued to us in those days consisted of képi, which was red with a blue band, blue tunic, red trousers, and a short vest which we called veste de singe, an overcoat and the blue woollen belt which it is compulsory to wear over our tunics as a precaution against dysentery. The couvre nuque was also issued but, in spite of the fact that in films about the Legion the officers and men are always shown wearing it, day and night, this is not so in reality. It is never worn. The only use to which it is put by Légionnaires is to strain their coffee or even water when it is very muddy! The epaulettes, which are also featured in films and fiction have not been worn since 1907. The only epaulette a Legion soldier wears is a little blue rosette of felt which he sews on his right shoulder in order to hitch his rifle over it. When we were in the Dardanelles in 1915 blue linen trousers called salopettes were issued to us to wear over our red ones. During the war, when the French troops got their bleu horizon, we were given khaki and since then all the French Colonial troops have worn khaki. The French Government bought up all the American uniforms at the end of the war.

Within a few hours of our arrival at Sidi Bel Abbes the battalion was entrained for Perrigaux. As we got there we heard firing and learned that the Arabs had attacked the town and that we had to push them back into the mountains. This attack on Perrigaux was the last Arab revolt in Algeria.

Our forces consisted of one battalion of the Legion, some French Colonial troops and a few Tirailleurs.

We dug a trench. We could see the Arabs only about two hundred yards away and knew that there were a lot more that we could not see, among the rocks at the foot of the hills. The rifle that was issued to us in those days was the fusil gras which had been in use since 1870. It was monstrously heavy and fired great big bullets. I had no idea how to use it but I lay down in the trench next to an old soldier and watched what he did. The first shot I fired there was a terrible kick which made my shoulder sore for days! I opened the bolt very carefully and slowly for fear of what would happen so that the ejector did not work and I had to poke the cartridge case out with a pencil!

The soldier next me laughed and showed me how to use the rifle and after that it was better and I began to enjoy firing it.

After an hour of this we were ordered to fix bayonets and charge. In a charge like this, it is the old soldiers, who have experience of colonial warfare and know how to take cover and watch out for the Arabs, who get through. On that charge nearly all the recruits who came up with me were killed.

I was not at all afraid and to my own surprise I was not even excited. I seemed to feel quite cool ; in those days I was unconscious of danger. I did not know what it meant. Every one was all over the place. I found myself face to face with an Arab and plunged my bayonet into him, but in doing so I turned it so that I could not get it out again and had to leave it in his body. The Arabs do not like facing steel and they began to ran away towards the mountains with our troops after them in any sort of order.

I had already been told that for every enemy killed a Légionnaire cuts a notch in his rifle and as I went on I got out my knife and started to make a notch on mine. It was very hot and I was dead tired with running over the rough ground and carrying the heavy rifle and kit, and so I sat down on a rock to rest. Suddenly I saw a party of Arabs quite near to me on the right. They closed round me and I realised that I was their prisoner but, not really knowing what that meant, I was not frightened and thought it best to be friendly so I offered them cigarettes. They took them and also took my cartridges away from me, but left me to carry the heavy rifle. I could not under-stand what they said but something in their faces and gestures alarmed me in an unexpected way, and when one of them started to put his hands on me in a nauseating, caressing way I upped with the butt of the rifle and smashed his head in. That ended all friendly relationship with my captors

When they got me back to their camp I was handed over to the women. It is the women who do the torturing. On the way up to Perrigaux in the train an old soldier had been telling of his adventures and had talked of having been taken prisoner by the Arabs. I remembered his saying that if this should happen to a man the only thing to do to escape torture was to pretend to be mad as the Arabs think that a madman is "possessed" by a spirit and will not touch him. So I thought I had better do this and I started catching flies where there were none, catching at my own thumb and making any idiotic face and gesture I could think of. When I saw them draw back from me I wanted to laugh, but I managed not to do so.

They put some food near me which I was glad of by then and in the evening they brought me to the Marabou (a sort of holy man or priest) who could speak French and he questioned me about the strength of the battalion. I don't think I even knew, but, anyway, I made up some tremendous number and all the time I was playing the fool to make him believe me mad.

The Arabs evidently did not think much of me as a prisoner for that night they took me down to the plain near where we had been fighting that day and signed to me to go back to our lines. But they had taken my rifle away from me and that bothered me very much. I did not want to go back without it. Already I had been made to understand that it was a terrible offence in the Legion to lose any part of your kit or equipment but also my rifle had that notch in it for my" first man." I went on for a few hundred yards towards Perrigaux and then I hid behind a bush and began wondering how on earth I could get my rifle back. The rest of the night I lay out there between the lines.

Early in the morning the Legion started to attack again and a lot of them came right past me. The Arabs ~ere shooting from behind their boulders and bushes and the Arab marksmen are deadly sure. They have any kind of rifle they can get hold of and they do not use the sights, but put two fingers on the barrel when they aim. A Legion soldier fell dead, shot through the head, within a yard of where I was hiding. Then I came out, made sure he was lifeless, picked up his rifle and joined in the attack.

When it was over I went to my Captain and reported. I told him all that had happened. He seemed to find it amusing, as I did when I started to talk about it, and he laughed and said he was pleased with me, that I was a good soldier. I felt very proud of that.

We quelled the Arab revolt in, I think, four or five days and then we went back to Sidi Bel Abbes.

When we were back in barracks I got in touch with an old soldier who promised to show me the ropes and put me wise to the ways of the Légionnaires. He was a very nice fellow, a bugler from Brittany called Le Gonnec.

When a man joins the French Foreign Legion the first thing he has to learn is the base de la discipline - the Legion's code.

It is : "La disciphne étant la force principale de la Légion il importe que tous superieurs obtiennent de ses subordonn6s une obeissance entiere et une soumission de tous les instants, que les ordres soient execute's instantanément, sans hesitation ni murmure, les autorités qui les donnent en sont responsable et Ia reclamation n'est permise a l'inférieur que lorsque qu'il a obei."*

*Discipline being the principal strength of the Legion it is essential that all superiors receive from their subordinates absolute obedience and submission on all occasions. Orders must be executed instantly without hesitation or complaint. The authorities who give them are responsible for them and an inferior is only permitted to make an objection after he has obeyed.

The second thing a Legionnaire must learn is how to get drunk when he has no money to buy wine!

In I914 there were three battalions and each battalion had four companies.

My company was the 9th of the 3rd battalion of the 1st regiment commanded by Captain Rousseau. He was a splendid officer and understood his men, having been a ranker himself. His old mother used to keep a canteen in Sidi Bel Abbes. Although there were the sergeants and corporals between them and the men, the good officers always studied their men and knew their characters, when to overlook their faults, when to punish, and how to get the best out of them.

A second-class soldier is an ordinary private. First-class soldiers are rare and are not thought anything of as, in order to gain this nebulous distinction, a man must have no punishment, and that is practically impossible for a real Légionnaire. The best soldiers in the fighting line spend a great deal of their time in prison when their battalion is in barracks.

I always hated parades and one morning when the sergeant who was drilling us had made us stand to attention and slope arms several dozen times, I began obeying slackly, just bending my knee and not moving my feet apart at the word repos and, when he went for me, I threw my rifle down on the ground. For this I was tied to a tree for the rest of the morning, with the woollen belt which, as I have said, we all wore, by orders, over our tunice. Afterwards I was reported to the Captain.

When he asked me why I had behaved like that, I said: I am intelligent enough to know how to stand at attention and slope arms after doing it once; I don't need to go on doing it fifty times an hour."

As a matter of fact, I was rather a favourite with Captain Rousseau. He knew my age, as indeed they all did (unofficially, of course) and he chose to overlook both my "crime" and my cheek.

He cautioned me that to refuse to obey a command meant court-martial and prison and told me not to do it again. But by his orders I was given a job in the store-room and so escaped those eternal and infernal parades. .

In February, 1915, it was posted in orders that any man who wished to do so could volunteer for active service. I think nearly the whole battalion wanted to. I was for rushing off to find the Captain to put my name down then and there. Some one tried to stop me and explained that I must go to the Corporal, who would forward my name to the Sergeant and he would give it to the Lieutenant for the Captain.

"Not I!" I called to them, as I went off. "I'm going straight to God, not to all his Saints first."

I found Captain Rousseau in the mess-room, saluted and said: If you please, sir, will you put my name down for active service ?

"That's all right, de Bruin" - he smiled -"You're down already.”

From Tiaret we were sent to Oran where we camped in an old Roman arena which is surrounded by a very high wall, the idea being that this would make it difficult for us to break camp and go into the town to drink. As a matter of fact, the authorities are never very optimistic about the success of their expedients in this direction. They know the Légionnaires too well. Those of us who were determined to get into the town that night fastened our leather belts together and so managed to 8cale those noble Roman walls.

Many are the ways in which a Legion soldier will earn drinks or the money to buy them. I used to go into the café and entertain people by blowing fire out of my mouth (a trick easily done with petrol) eating the red-hot end of my cigarette (the doctors say it is good for the stomach I) and piercing my cheeks with needles or pins. This does not hurt in the least if you do it quickly enough. The price of these edifying exhibitions was enough wine to keep me happy for the evening.

So well do the authorities know what is going on that they send out patrols to bring the truants back under arrest, some-times unconscious. But there is no punishment on the eve of going into action.

The morning after we camped at Oran, half the battalion was missing, but Legionnaires do not desert when they know they are going to fight and gradually they came in. Some turned up even without hats and other parts of their kit when we were on the quay ready to embark, but the battalion left Oran full strength.

We went on La France, which had been a passenger boat plying between Marseilles to Tunis. She had been converted into a troopship. At Malta we had to stay on board and we were disembarked at Alexandria. There we were attached to the Rdgiment de Marche d'Afrique, composed of volunteers from regular French regiments, under General d'Amade. We camped at the back of the Victoria Hospital on English territory. We still did not know our destination.

We had been kept hanging about, on the boat and at Alexandria, for over two months. There was a shortage of cigarettes and wine and there was a faction in the battalion which began to be actively discontented and to discuss whether it would not be a good thing to desert. We were on English territory and the idea was that if we could get away we might join the English forces and see some of the fighting for which we had volunteered. I was young and easily led and anything that sounded like an adventure was in my line so I threw in my lot with about forty men who decided to get away. It was a very abortive effort at desertion and we were caught and brought back to camp under arrest.

Then orders came through that there was to be a review. Whether this was intended to occupy us or impress some one else, I don't know; but on account of it those under arrest were released and put back into the lines. When the review was over we were again put under arrest.

At last we were embarked on the Bien Hoa, one of the ships which had relieved Casablanca when the town was captured by the Arabs in 1907.

It was a relief to know that we were on our way somewhere, presumably to the fighting line and, on board, those under arrest were released.

Thursday 15 March 2012

Wednesday 14 March 2012

Tuesday 13 March 2012

Monday 12 March 2012

Saturday 10 March 2012

Friday 9 March 2012

Thursday 8 March 2012

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

hg~~60_12.JPG)

3+BPFZeIvqOg~~60_3.JPG)

28zVBOWOoTmDqg~~60_12.JPG)

uTz!~~60_12.JPG)

QZuiQ~~60_12.JPG)