One of the best ever toy soldiers ever made and imagine if it was painted bettter how authentic it would be, compare it to the Remington images.

One of the best ever toy soldiers ever made and imagine if it was painted bettter how authentic it would be, compare it to the Remington images.The historic American cowboy of the late 19th century arose from the vaquero traditions of northern Mexico and became a figure of special significance and legend. A subtype, called a wrangler, specifically tends the horses used to work cattle. In addition to ranch work, some cowboys work for or participate in rodeos.

There are also cattle handlers in many other parts of the world, particularly South America and Australia, who perform work similar to the cowboy in their respective nations.

The cowboy has deep historic roots tracing back to Spain and the earliest European settlers of the Americas. Over the centuries, differences in terrain, climate and the influence of cattle-handling traditions from multiple cultures created several distinct styles of equipment, clothing and animal handling.

Over the centuries, differences in terrain, climate and the influence of cattle-handling traditions from multiple cultures created several distinct styles of equipment, clothing and animal handling. As the ever-practical cowboy adapted to the modern world, the cowboy's equipment and techniques also adapted to some degree, though many classic traditions are still preserved today.

As the ever-practical cowboy adapted to the modern world, the cowboy's equipment and techniques also adapted to some degree, though many classic traditions are still preserved today.

Over the centuries, differences in terrain, climate and the influence of cattle-handling traditions from multiple cultures created several distinct styles of equipment, clothing and animal handling.

Over the centuries, differences in terrain, climate and the influence of cattle-handling traditions from multiple cultures created several distinct styles of equipment, clothing and animal handling. As the ever-practical cowboy adapted to the modern world, the cowboy's equipment and techniques also adapted to some degree, though many classic traditions are still preserved today.

As the ever-practical cowboy adapted to the modern world, the cowboy's equipment and techniques also adapted to some degree, though many classic traditions are still preserved today.

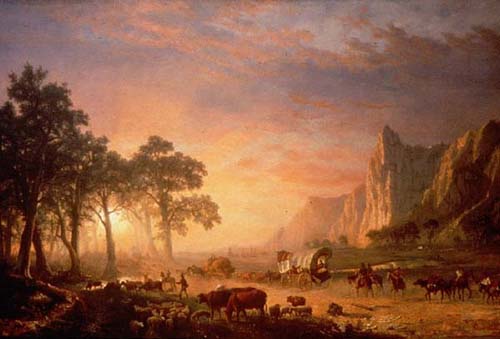

The migration would explode in 1849's "The Forty-Niners" in response to the discovery of gold in California in 1848. Manifest Destiny had received a powerful push in the spring and summer of 1846 with the international treaties settling the ownership of the Pacific coast territories and the Oregon Country on the United States.

The migration would explode in 1849's "The Forty-Niners" in response to the discovery of gold in California in 1848. Manifest Destiny had received a powerful push in the spring and summer of 1846 with the international treaties settling the ownership of the Pacific coast territories and the Oregon Country on the United States.

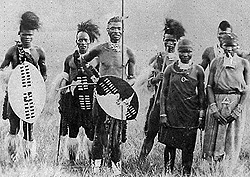

One reason that the British harbor such a visceral hatred for Sudan, is that they have never fully recovered from their experience with the Mahdist state, which lasted from the early 1880s to 1898.

One reason that the British harbor such a visceral hatred for Sudan, is that they have never fully recovered from their experience with the Mahdist state, which lasted from the early 1880s to 1898.

The massacre of Hicks's force was hard for the British to comprehend. Gordon is reported to have believed that they all died of thirst, and that no military encounter had even taken place! The fall of Shaykan led to the success of the Mahdist revolt in Darfur and Bahr al-Ghazal, and the continuing attachment of tribal units to the Ansar forces.

The massacre of Hicks's force was hard for the British to comprehend. Gordon is reported to have believed that they all died of thirst, and that no military encounter had even taken place! The fall of Shaykan led to the success of the Mahdist revolt in Darfur and Bahr al-Ghazal, and the continuing attachment of tribal units to the Ansar forces.

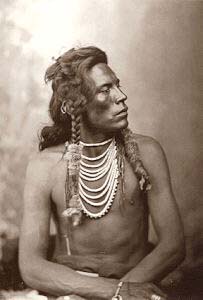

best known for having been one of the few survivors on the United States side at the Battle of Little Bighorn. He did not fight in the battle, but watched from a distance, and was the first to report the defeat of the 7th Cavalry Regiment.

best known for having been one of the few survivors on the United States side at the Battle of Little Bighorn. He did not fight in the battle, but watched from a distance, and was the first to report the defeat of the 7th Cavalry Regiment.

.jpg)

His name, variously rendered as Ashishishe, Shishi'esh, etc., literally means "the Crow".

His name, variously rendered as Ashishishe, Shishi'esh, etc., literally means "the Crow". and married Bird Woman. He enlisted in the U.S. Army as an Indian scout on April 10, 1876. He served with the 7th Cavalry Regiment under George Armstrong Custer,

and married Bird Woman. He enlisted in the U.S. Army as an Indian scout on April 10, 1876. He served with the 7th Cavalry Regiment under George Armstrong Custer,  and was with them at the Battle of Little Bighorn in June of that year, along with fellow Crow warriors White Man Runs Him, Goes Ahead, Hairy Moccasin and others.

and was with them at the Battle of Little Bighorn in June of that year, along with fellow Crow warriors White Man Runs Him, Goes Ahead, Hairy Moccasin and others. Curly and the other scouts did not participate in the battle, but were ordered away before the fighting began. Curly evidently watched the battle from a distance, and, seeing Custer's defeat was imminent, rode off to report the news.

Curly and the other scouts did not participate in the battle, but were ordered away before the fighting began. Curly evidently watched the battle from a distance, and, seeing Custer's defeat was imminent, rode off to report the news.

. He was the first to report the 7th's defeat, using a combination of sign language, drawings, and an interpreter. Curly did not claim to have fought in the battle, below lead charbens

. He was the first to report the 7th's defeat, using a combination of sign language, drawings, and an interpreter. Curly did not claim to have fought in the battle, below lead charbens

(who interviewed Curly on several occasions) and John S. Gray, accepted Curly's early account. Later, however, when accounts of "Custer's Last Stand" began to circulate in the media, a legend grew that Curly had actively participated in the battle but had managed to escape. Later on, Curly himself stopped denying the legend, and offered more elaborate accounts in which he fought with the 7th, and had avoided death by disguising himself as a Lakota warrior, leading to conflicting accounts of his involvement.

(who interviewed Curly on several occasions) and John S. Gray, accepted Curly's early account. Later, however, when accounts of "Custer's Last Stand" began to circulate in the media, a legend grew that Curly had actively participated in the battle but had managed to escape. Later on, Curly himself stopped denying the legend, and offered more elaborate accounts in which he fought with the 7th, and had avoided death by disguising himself as a Lakota warrior, leading to conflicting accounts of his involvement. He divorced Bird Woman in 1886, and married Takes a Shield. Curly had one daughter, Awakuk Korita ha Sakush ("Bird of Another Year"), who took the English name Nora. For his Army service Curly received a U.S. pension as of 1920. He died of pneumonia in 1923, and his remains were interred in the National Cemetery at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, only a mile from his home.

He divorced Bird Woman in 1886, and married Takes a Shield. Curly had one daughter, Awakuk Korita ha Sakush ("Bird of Another Year"), who took the English name Nora. For his Army service Curly received a U.S. pension as of 1920. He died of pneumonia in 1923, and his remains were interred in the National Cemetery at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, only a mile from his home.

and his seven companies, moved to the right around the base of a hill overlooking the valley of the Little Horn, through a ravine just wide enough to admit his column of fours.

and his seven companies, moved to the right around the base of a hill overlooking the valley of the Little Horn, through a ravine just wide enough to admit his column of fours.  There was no sign of the presence of Indians in the hills on that side (the right) of the Little Horn, and the column moved steadily on until it rounded the hill and came in sight of the village lying in the valley below them. Custer appeared very much elated and ordered the bugle to sound a charge, and moved on at the head of his column, waving his hat to encourage his men.

There was no sign of the presence of Indians in the hills on that side (the right) of the Little Horn, and the column moved steadily on until it rounded the hill and came in sight of the village lying in the valley below them. Custer appeared very much elated and ordered the bugle to sound a charge, and moved on at the head of his column, waving his hat to encourage his men. When they neared the river the Indians, concealed in the underbrush on the opposite side of the river, opened fire on the troops, which checked the advance. Here a portion of the command were dismounted and thrown forward to the river, and returned the fire of the Indians.(De Rudio)

When they neared the river the Indians, concealed in the underbrush on the opposite side of the river, opened fire on the troops, which checked the advance. Here a portion of the command were dismounted and thrown forward to the river, and returned the fire of the Indians.(De Rudio)

The horses were in the rear, the men on the line being dismounted, fighting on foot. Of the incidents of the fight in other parts of the field than his own,

The horses were in the rear, the men on the line being dismounted, fighting on foot. Of the incidents of the fight in other parts of the field than his own, Curley is not well informed, as he was himself concealed in a ravine, from which but a small portion of the field was visible.

Curley is not well informed, as he was himself concealed in a ravine, from which but a small portion of the field was visible.

The Indians had completely surrounded the command, leaving their horses in ravines well to the rear, themselves pressing forward to attack on foot. Confident in the superiority of their numbers, they made several charges on all points of Custer's line, but the troops held their position firmly, and delivered a heavy fire, and every time drove them back.

The Indians had completely surrounded the command, leaving their horses in ravines well to the rear, themselves pressing forward to attack on foot. Confident in the superiority of their numbers, they made several charges on all points of Custer's line, but the troops held their position firmly, and delivered a heavy fire, and every time drove them back. Curley said the firing was more rapid than anything he had ever conceived of, being a continuous roll, as he expressed it, "the snapping of the threads in the tearing of a blanket. The troops expended all the ammunition in their belts, and then sought their horses for the reserve ammunition carried in their saddle pockets.

Curley said the firing was more rapid than anything he had ever conceived of, being a continuous roll, as he expressed it, "the snapping of the threads in the tearing of a blanket. The troops expended all the ammunition in their belts, and then sought their horses for the reserve ammunition carried in their saddle pockets.